How is the aligner done?

Step 1: Take the shot

When your podiatrist has thoroughly examined your legs and feet, measured the required size, looked at your shoes, and asked about your lifestyle, she would shape the foot for you.

As we mentioned before, it is important that your podiatrist take a non-weight plaster to your feet. The most common method of making this gypsum is to use plaster. The wet plaster strip is wrapped around the foot. The hollow "negative foot mold" is sent to the orthopedic laboratory where the laboratory fills the casting and discards the outer casing. The resulting "frontal plaster" looks like your feet.

Remember, your feet should be cast :

In a non-weight-bearing way (you need to sit or lie down)

In a neutral position (your podiatrist should let you roll up your pants so they can see the relationship between the knees and feet and adjust the feet accordingly)

When the plaster becomes hard, your podiatrist should wait with you to observe the position of your foot (usually 5 to 10 minutes). Gypsum usually takes a full 24 hours to fully harden, so when your podiatrist takes them off your feet, she puts them in a safe place and sends them to the lab.

How is the aligner done?

Step 2: Lab

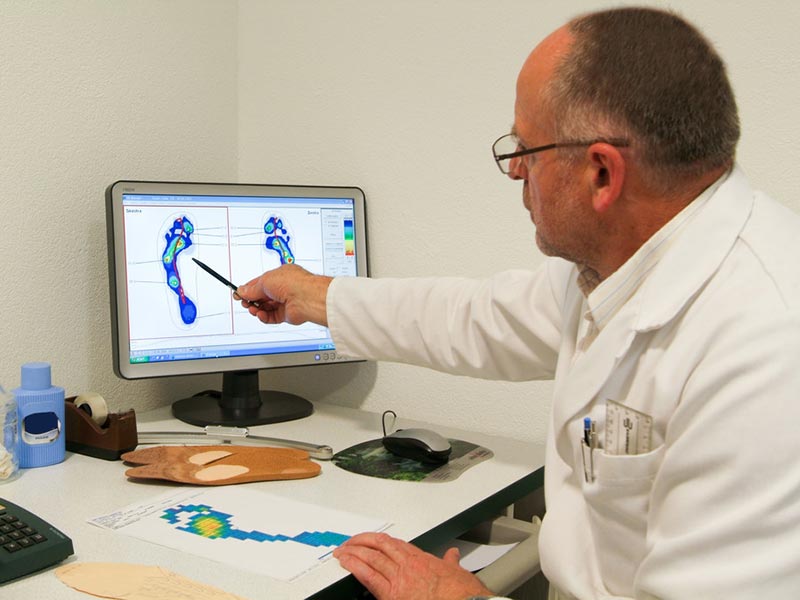

When your podiatrist has made the right weightless plaster for your foot, she will send your negative foot mold and your custom prescription to the correction lab. Your prescription will include not only materials, dimensions and accessories for the manufacture of orthoses, but also standardized correction castings. These measurements are based on an in-depth examination performed by the podiatrist before you step down.

This is where the custom insole is different from the clamshell model. Your podiatrist will detail how to design the orthosis to correct the biomechanical irregularities of your foot (as shown). A crappy box will simply implant these biologically irregular things into the corrector itself.

Once the positive film is cast, the lab will build the positive orthosis by following these steps:

At extreme temperatures, your castings are pressed against graphite or plastic materials.

A cover made of a comfortable and durable material is attached to the harder heel and arch.

How is the aligner made?

Part III: Materials

To provide the best results for your custom orthotic insoles, they must be made of materials that can withstand all kinds of strength and movement that you put on your feet. In this sense, the material needs to be rigid enough to control the irregular movement that produces damage while being flexible and comfortable enough to fit your activity. There are two main types of materials for your orthopedic rigid foundation:

Plastics - Most plastics come from the polyolefin family. Polypropylene is the most commonly used plastic.

Material thickness is usually between 1/8" and 1/4".

Plastics have a wide range of flexibility, ranging from very flexible to relatively rigid

Graphite - The graphite family is lighter and thinner than plastic.

Material thickness is half the thickness of the plastic (1/16" to 1/8")

Also has a wide range of flexibility and rigidity

Cushioning materials such as neoprene and open and closed cell forms are often used to supplement hard plastic or graphite and provide extra comfort. Remember, these softer materials should never form the core structure of your orthotics.

The most commonly used materials are used to cover plastic or graphite arch supports and heel cups from the family of polyethylene foam. These are the best all-contact, decompression orthopedics in closed cell form. Personal information includes:

Ethyl-vinyl cetates (eva)

French pancakes / neoprene

Silicone