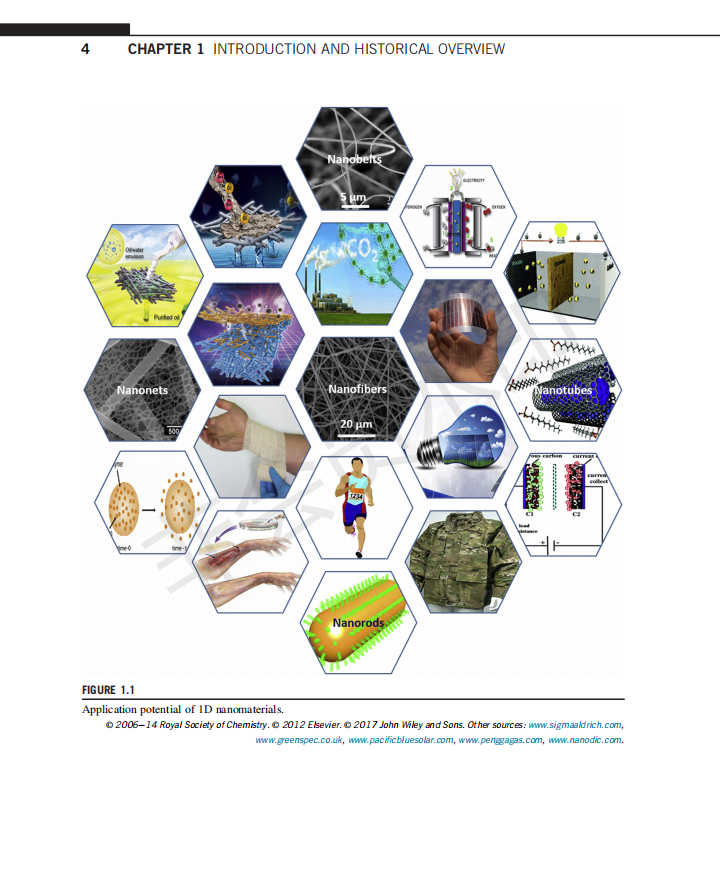

Nowadays, nanomaterials are at the center of attention of engineers and scientists because of their ability to alter the performance and capabilities of materials in a number of commercial sectors (Fang et al., 2008, 2011; Zhang and Fang, 2010; Xiao et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013). Nanomaterials are believed to be at the forefront of the fundamental materials because they provide additional features and aptitudes while maintaining the basic characteristics of the materials. Among all nanomaterials, one-dimensional (1D) nanostructured materials have firmly gained tremendous attraction in recent decades owing to their fundamental features, unique shapes, and potential applications in various fields (Lu et al., 2011; Yuan et al., 2011; Xia et al., 2003). These materials have enough potential to be applied to a very wide range of applications (Fig. 1.1).

Their characteristic features, such as high volume-to-surface area, facilitate the production of lighter weight materials, which is one of the key demands of all manufacturing fields; their ability to be highly hydrophobic and breathable is extremely desired for protective clothing; and their highly porous structure makes them ideal candidates for energy and environmental applications. Hollow fibers with multiple numbers of channels are a value addition in the field of biomedical and tissue engineering. The controlled structures of nanofibers developed from biodegradable and biocompatible sources such as polysaccharides and proteins are very useful in biomedical applications and regulated drug-delivery applications. Moreover, their individual fibers as well as resultant membrane structure can be custom-made to meet the needs of a number of applications. In addition, the growing interest of scientists in using nanofibers in various applications highlights the significance of their potential (Li and Yang, 2016; Kaur et al., 2014), which may also be credited to the easier fabrication with a variety of structural architectures and relatively reasonable production cost.